If you’re looking forward to the start of fall, you’re not alone—we are too because summer in Arizona is brutal! September will be a great time to visit national parks, such as Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming and Maine’s Acadia National Park, according to Earth Trekkers. It’s a classic American road trip that’s the perfect fit for another American classic: the Chevrolet Suburban, one of which happens to be our Pick of the Day. You can find this 1972 Chevrolet Suburban listed on ClassicCars.com by a dealer in Englewood, Colorado.

Consider this Suburban part of the end of an era. As a 1972, it’s from the final model year of the legendary model’s sixth generation that debuted for 1967. After this, it was nearly 20 years of the “Square Body” version that ran through 1991.

The 1972 model year was also the last time Chevrolet offered a three-door Suburban: one door on the driver’s side and two on the passengers’ side.

The unusual door layout could lead to you being the only one getting in on your side but, once your passengers load into the bright blue vinyl and cloth interior, they’ll have room for their luggage behind the second row bench and enjoy the comfort of the optional front and rear air conditioning system (once it’s recharged).

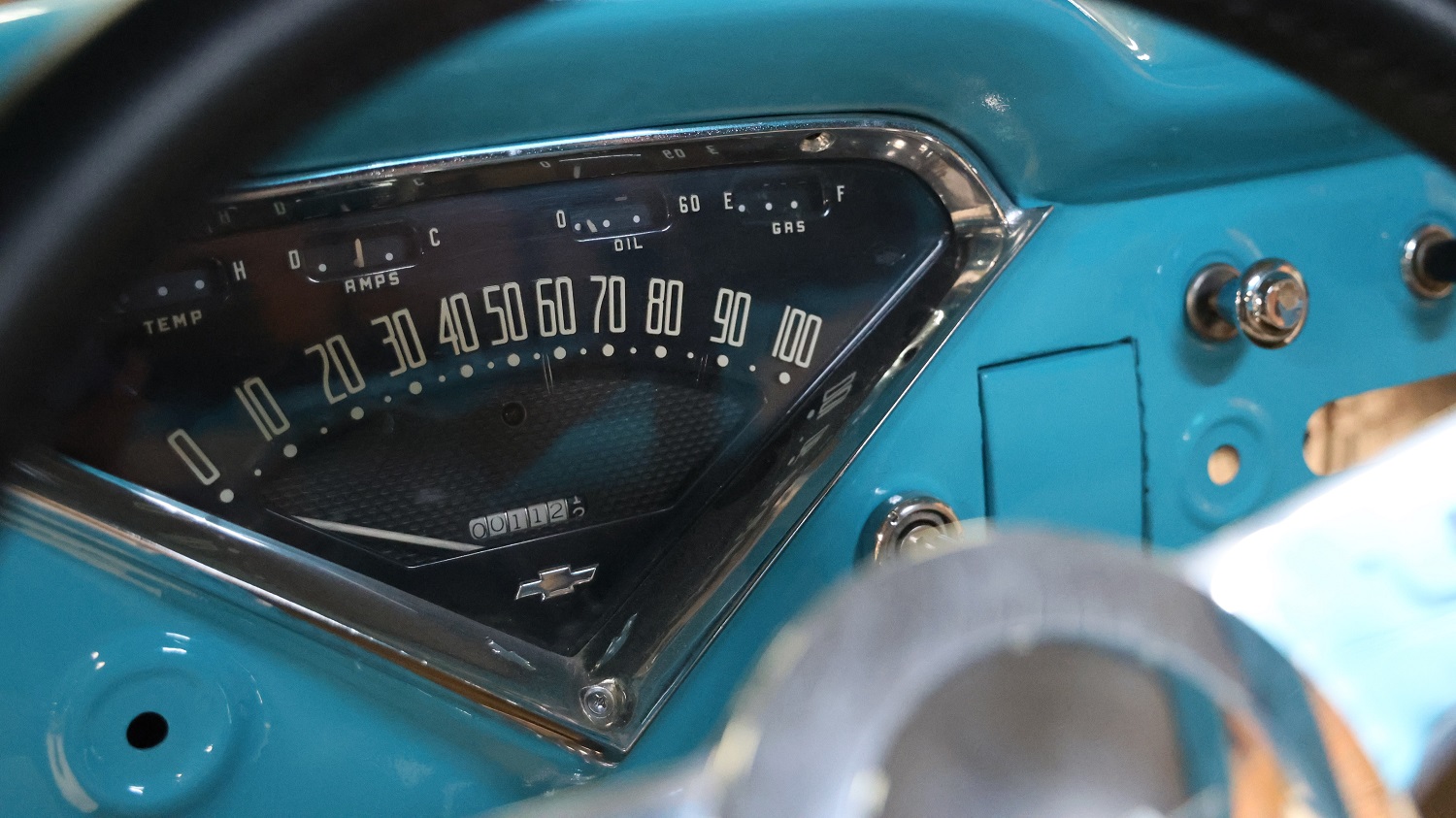

As the driver, you’ll appreciate the air conditioning as well as the convenience of power steering, three-speed Turbo Hydra-matic, cup holders, and gauges for the battery, temperature, and oil pressure (there’s never a good time for the engine to overheat, but one of the worst is halfway through a 10-hour out-of-state trip).

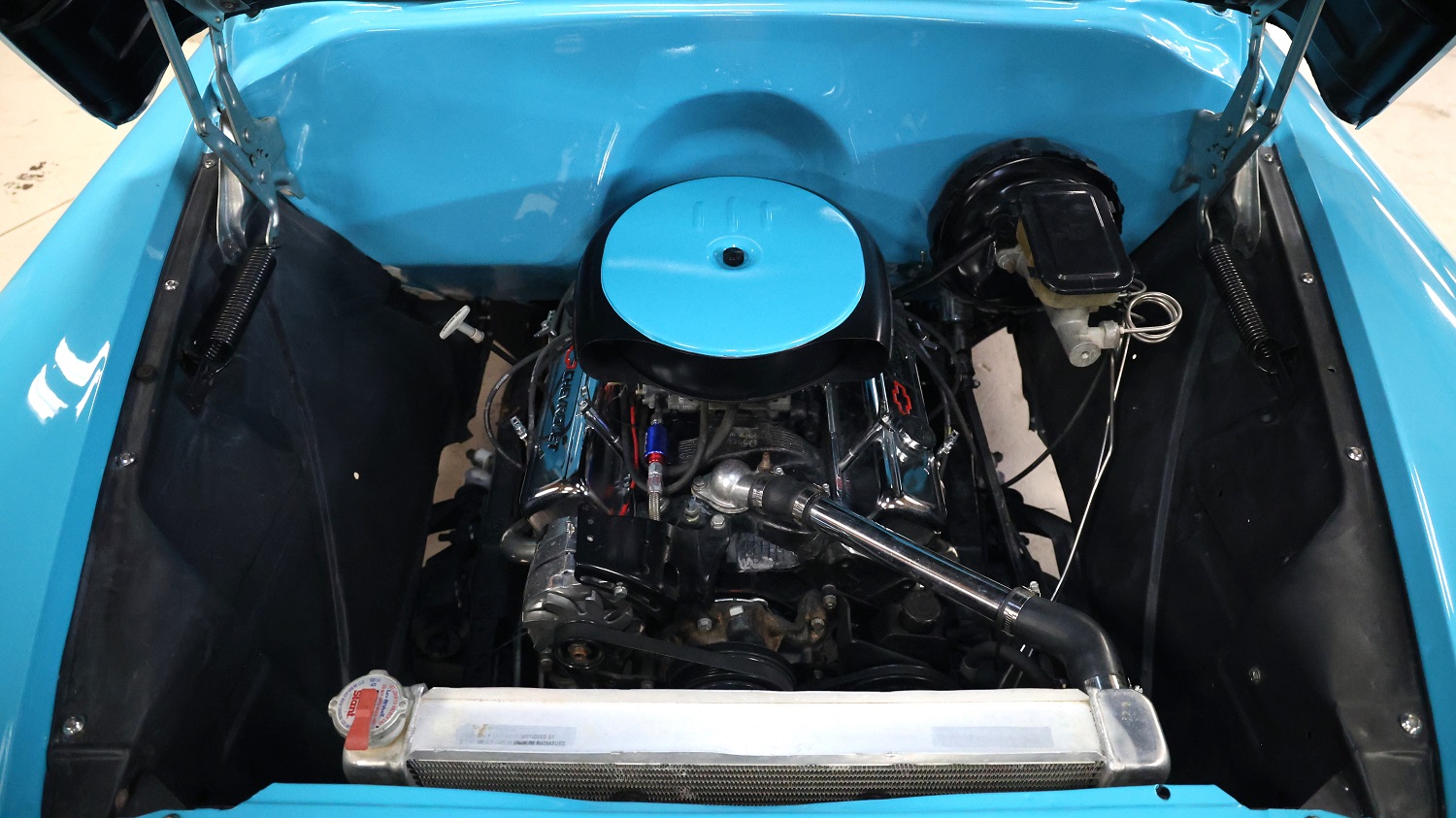

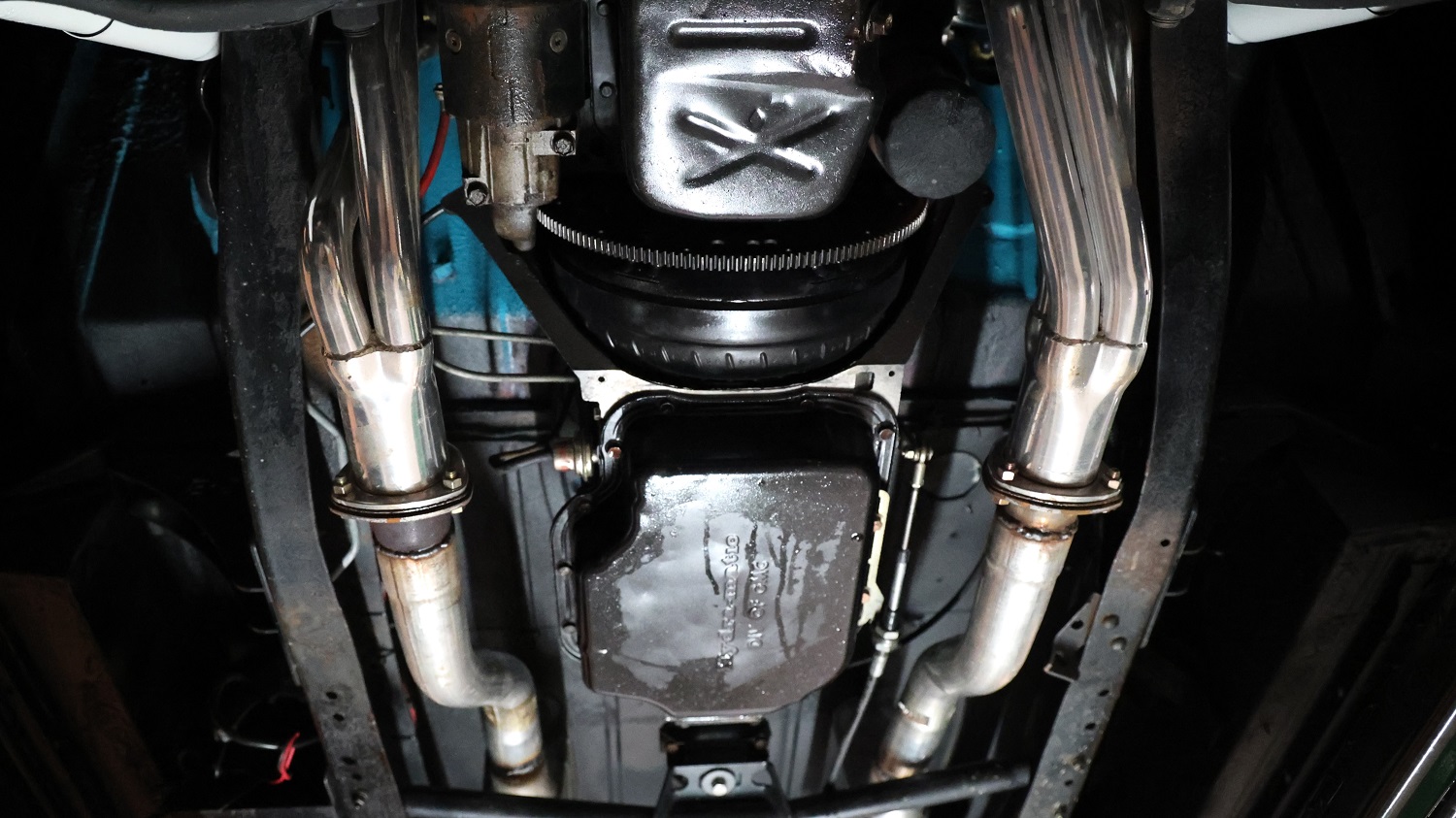

A good, old-fashioned 350ci small-block and a set of Rally wheels with BFGoodrich Radial T/A tires will get you and your family and/or friends on the way to the park of your choice. Power front disc and rear drum brakes will help each of you get there in one piece (it’s much easier to enjoy the view from the top of a mountain that way).

Fall is getting closer and closer, and this 1972 Chevrolet Suburban C10 Custom Deluxe might not be available by the time it arrives. You can officially start planning your trek to one of our country’s majestic national parks once you buy this iconic people-mover for $36,900.

Click here to view this Pick of the Day on ClassicCars.com