This 1931 Ford Model A coupe is a five-window steel hot rod that was reportedly acquired by the seller as a project in 2005 and subsequently was refurbished and modified beginning in 2011. Power comes from a Buick-sourced 425ci Nailhead V8 mated to a 700R4 four-speed automatic transmission and a narrowed Ford 9″ axle. The car is finished in blue with pinstriping over red custom upholstery, and additional work included chopping the roof 4″ and installing a Walden Speed Shop steel roof insert, later-model frame rails and radiator grille shell, a Rootlieb hood, Packard taillights, staggered-diameter steel wheels, modified suspension and braking components, an Edelbrock four-barrel carburetor, lake-style dual exhaust pipes, an American Autowire wiring harness, a 14-gallon fuel tank, and a Vintage Air heater. The refurbishment work is said to have been completed in February 2013, and service since 2021 has included replacing the windshield frame, front brakes, rear axle, and tires. This Ford hot rod is now offered with a car cover, touch-up paint, floor mats, refurbishment records and photos, and a Nevada title in the seller’s name.

![]()

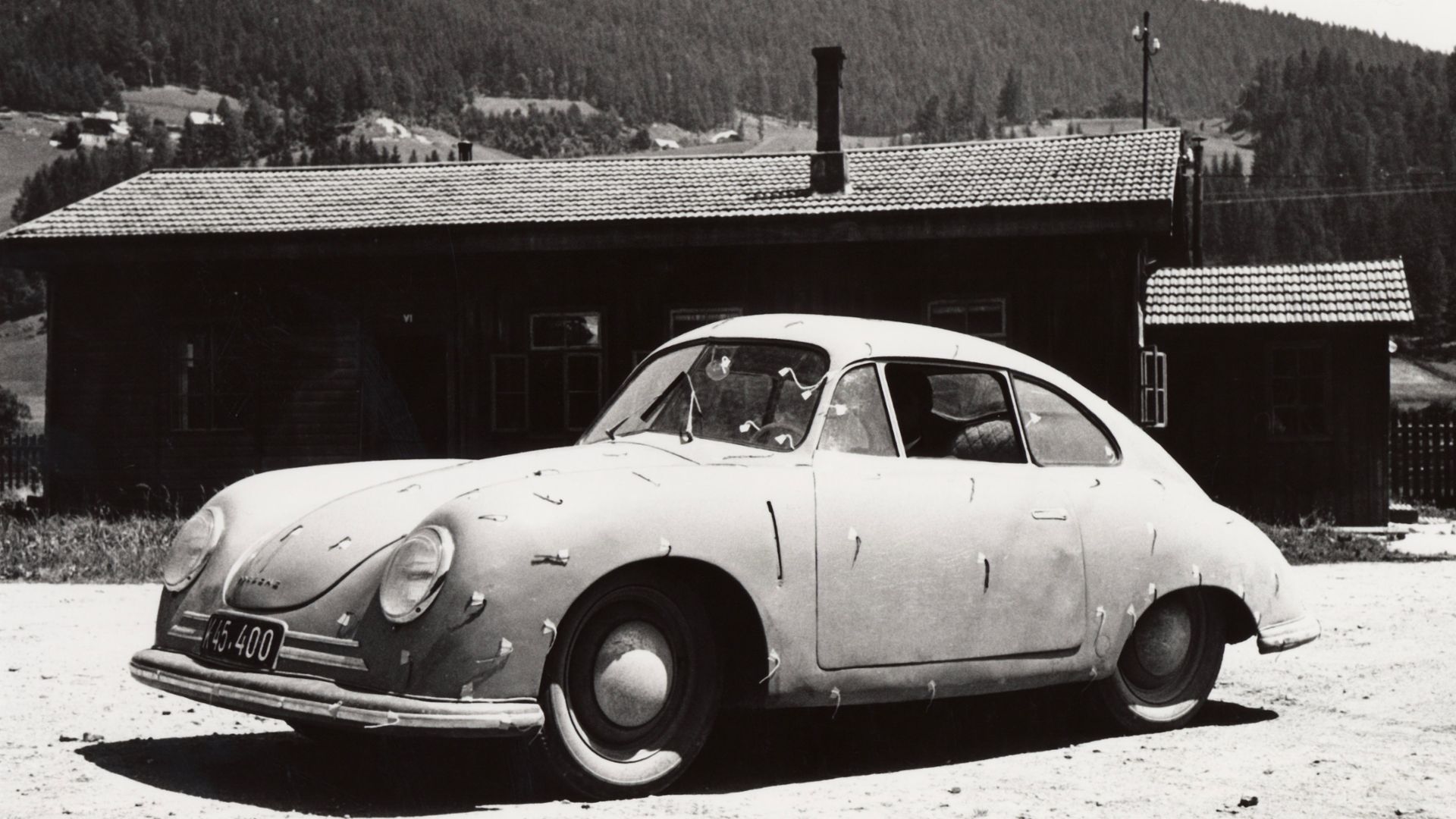

The steel five-window coupe body is said to have been modified during the aforementioned 2011–2013 refurbishment with work that involved removing the fenders, repairing rust, removing the cowl-mounted fuel tank and filling holes, performing a 4″ roof chop, fabricating rain gutters, and installing Cubel FordWood body framing, a Walden Speed Shop steel roof insert, replacement floors and glass, 1940s Packard–style taillights with LED elements, front turn signals, and a Rootlieb hood as well as boxed frame rails and a 1932 Ford–style radiator grille shell. The car reportedly has been refinished in Washington Blue, and multi-color pinstripes decorate the radiator shell and the trunk deck. Exterior wear includes a paint crack in the roof, an indentation in the rear wheel-well panel, a paint defect in the trunk panel, and other chips and scratches.

![]()

Black-finished 15″ front and 16″ rear steel wheels wear chrome hubcaps and trim rings as well as 5.60×15″ and 750×16″ Diamond Back Auburn radial tires that the seller states were installed in March 2022. Braking is handled by Walden Speed Shop Kinmont-style front discs with Wilwood four-piston calipers plus rear drums that are said to have been sourced from a Ford pickup truck. Front brake components were replaced in March 2022, and the steering and suspension have been modified and are said to feature the following components:

- Dropped and drilled Super Bell front axle

- Walden Speed Shop alloy front hubs with Ford spindles

- SoCal Speed Shop front Panhard bar

- Ford Mustang–sourced steering box

- QA1 adjustable rear coilovers

- Rear Panhard bar and ladders bars

![]()

The interior is equipped with low-back bucket seats trimmed in red marine-grade upholstery with stainless-steel trim, with a color-coordinated headliner and trim panels. Appointments include gray square-weave carpeting, a Vintage Air heater, a Lokar shifter, lap belts, and hand-crank side windows.

![]()

A three-spoke steering wheel fronts a body-color 1934 Ford–sourced steel dash fitted with aftermarket instrumentation that includes a 120-mph speedometer, auxiliary gauges, a column-mounted tachometer, and a transmission-fluid temperature gauge mounted inside the glove compartment. The digital odometer indicates 11k miles, which is said to reflect the distance accumulated since completion of the build. True chassis mileage is unknown.

![]()

A rearward-opening lid provides access to a trunk compartment that houses color-coordinated upholstery as well as a 14-gallon fuel tank.

![]()

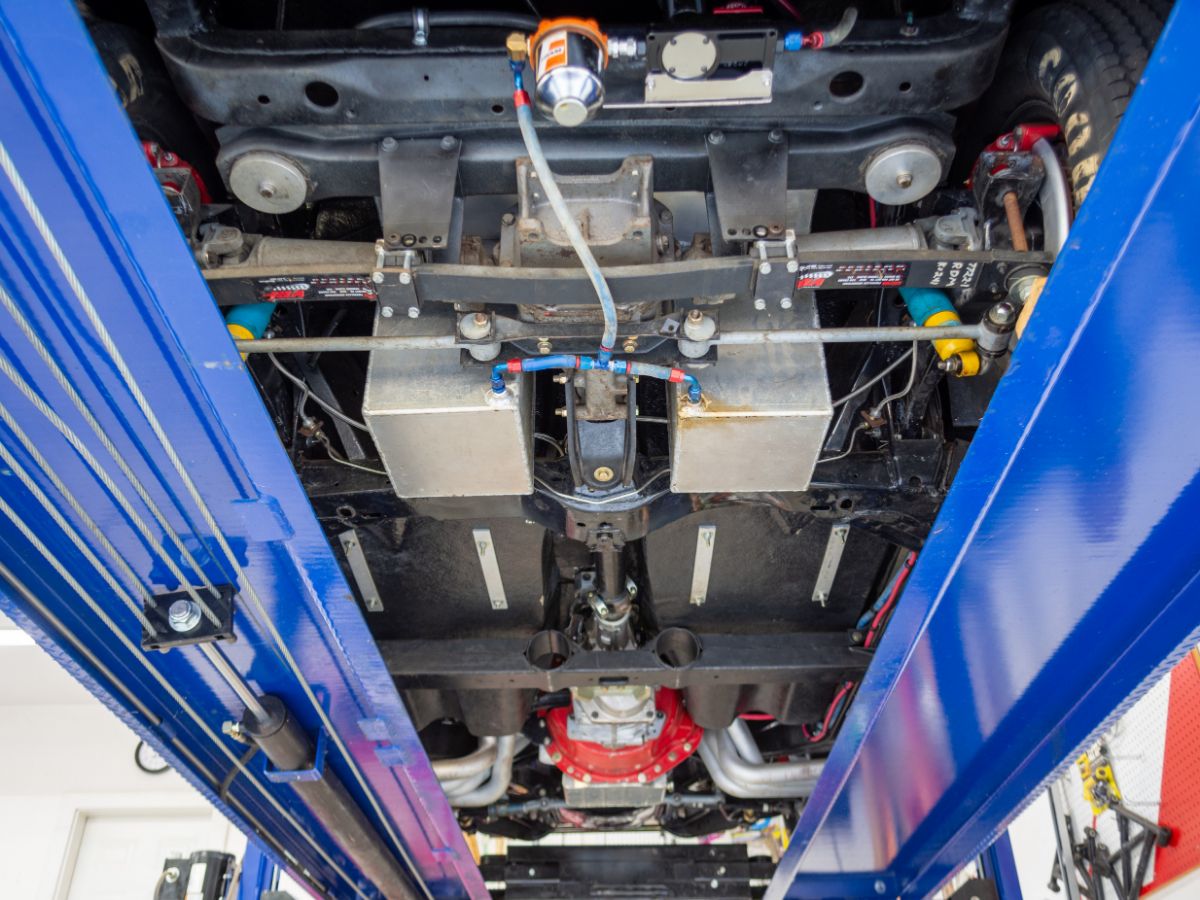

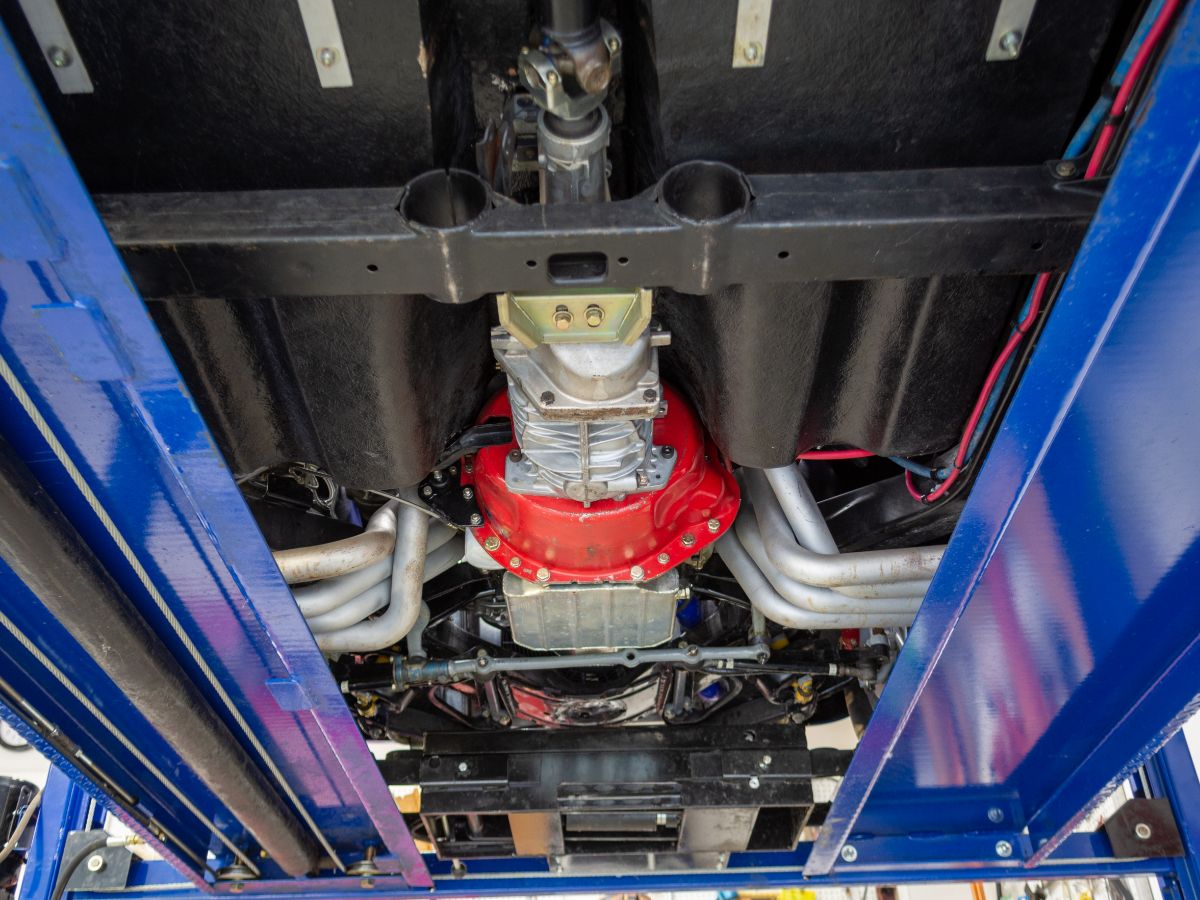

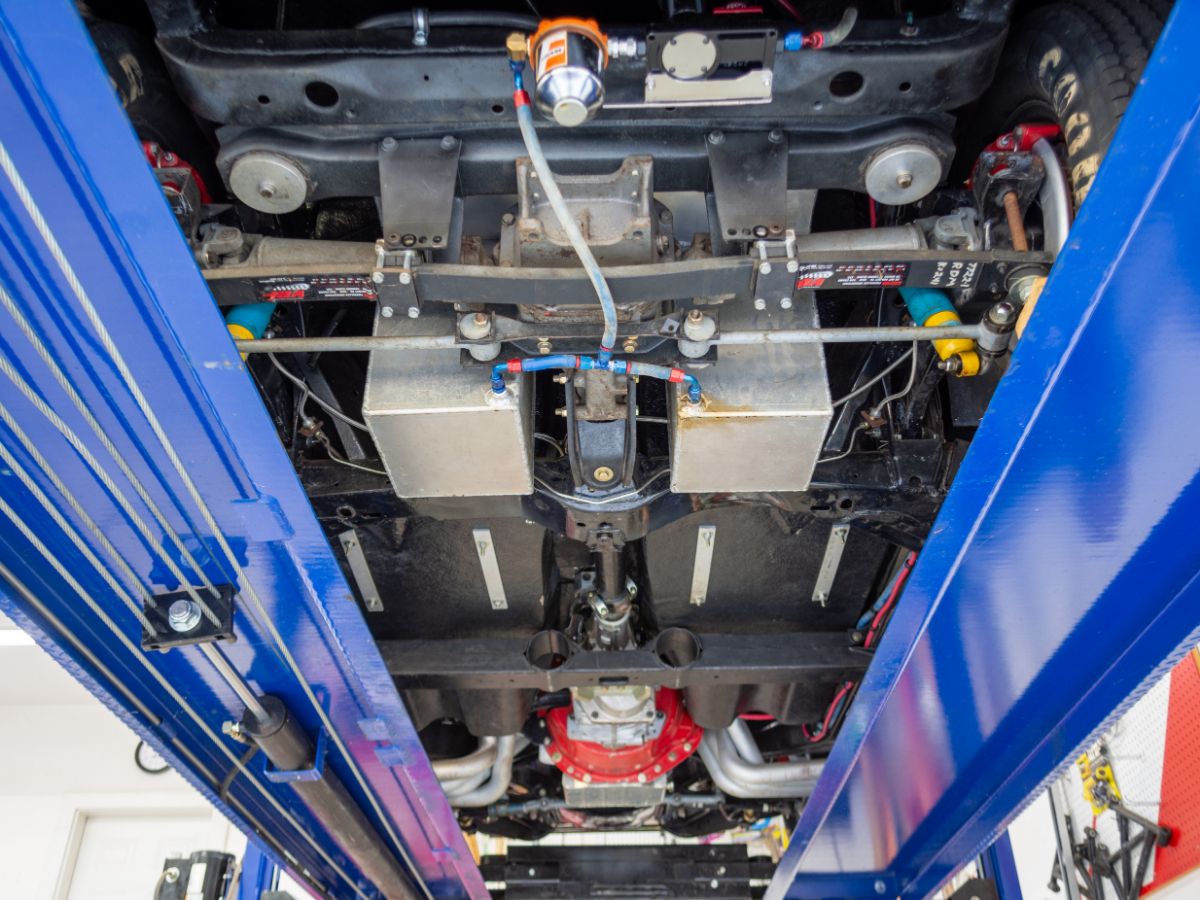

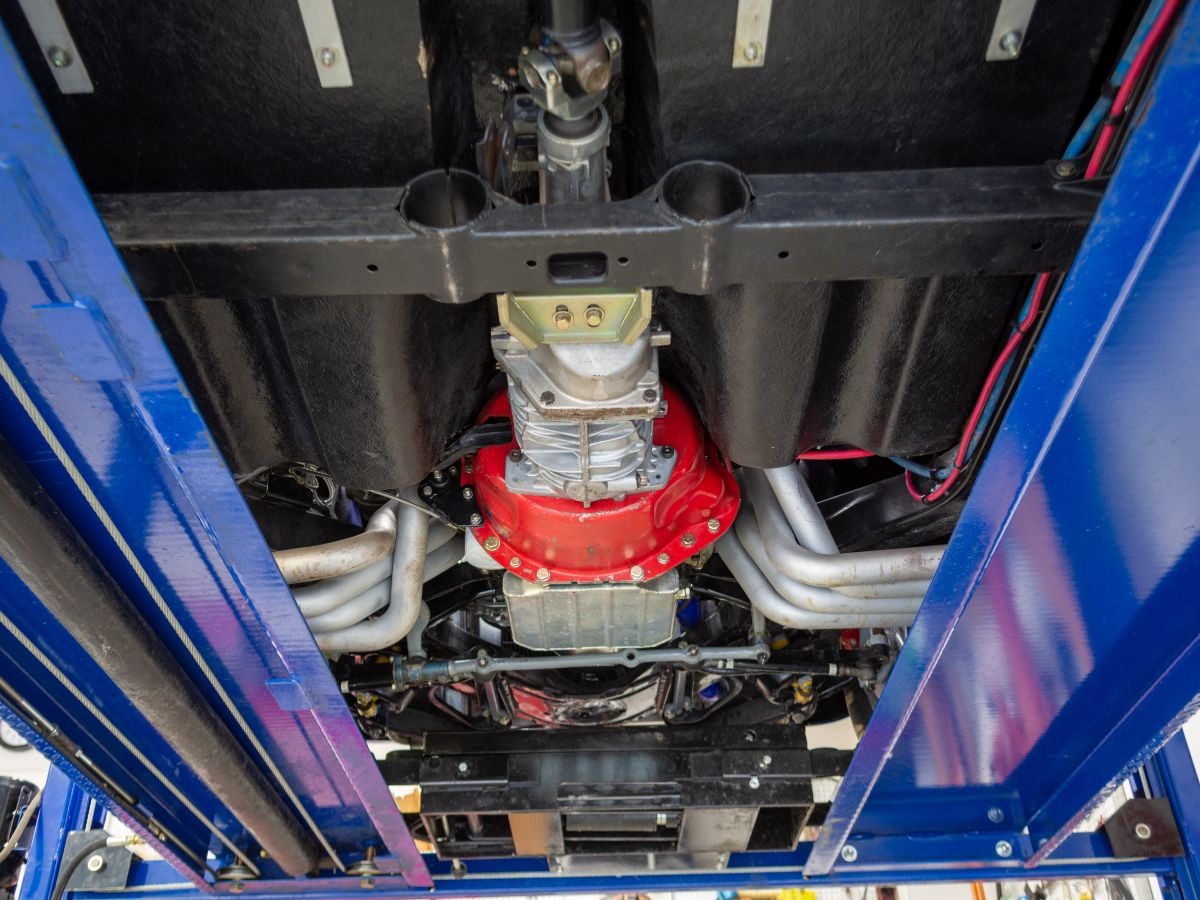

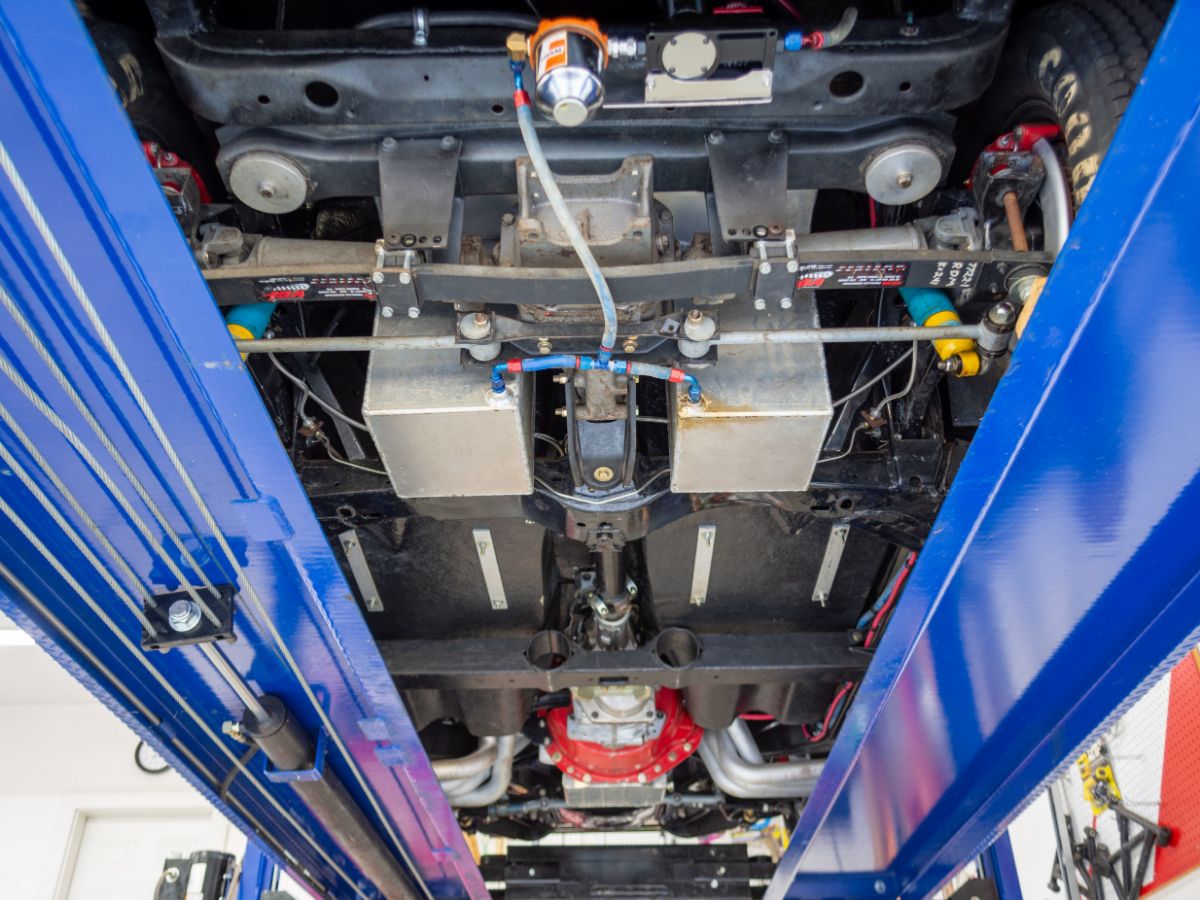

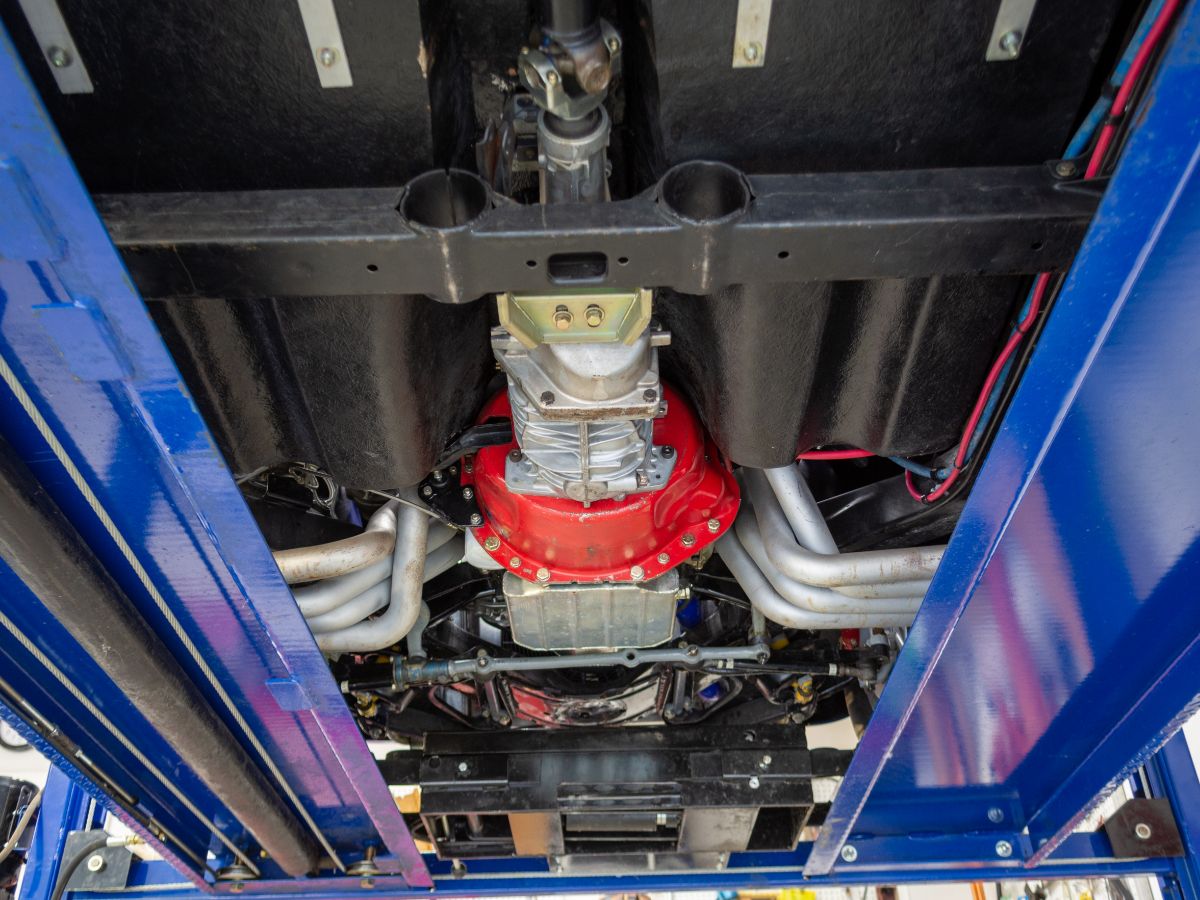

The 425ci Buick Nailhead V8 is equipped with an Elgin camshaft, an Edelbrock Performer four-barrel carburetor, a dual exhaust system with lake-style side pipes with cutouts, a Walker Radiator Works radiator, and an American Autowire wiring harness. The firewall reportedly was refinished in Wimbledon White with pinstripe accents. Power is sent to the rear wheels through a GM-sourced 700R4 four-speed automatic transmission and a narrowed Ford 9″ rear housing with Dutchman axles and a 3.70:1 gearset. The transmission is said to have been rebuilt by Bowtie Overdrives of Hesperia, California, and replacement Dutchman Motorsports axles were installed in January 2021 when the housing was narrowed.

![]()

Further work to the frame is said to have included boxing the outer rails, fitting a square-tube K-member and a C-notch, and shortening the rear frame horns. The seller states that the body is set back 4″ on the frame.

![]()

Additional photos documenting various stages of the refurbishment can be viewed in the gallery below.

![]()

The car was reportedly exhibited at the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada in 2021.

![]()

Documentation accompanying the vehicle includes two binders of refurbishment records and photos.

The Nevada title lists “Exempt” under the Odometer Brand section.